by Dr Ross Colquhoun, Consultant to Drug Free Australia – March 26, 2025

Summary:

Key Findings:

1. Mortality and Relapse Risks – Research indicates that opioid-dependent individuals face heightened mortality risks when starting or discontinuing methadone treatment and, to a lesser extent, while in MMT. Reviews have consistently found no significant difference in mortality and criminality between those in MMT and those who have not been in treatment. Studies suggest that methadone is a significant factor in the recent increase in overdose-related deaths, as shown by the disproportionate numbers of overdose deaths associated with the prescribing of methadone for chronic pain relief in the US.

2. Long-Term Dependency and Treatment Retention – Methadone is found to retain more people in treatment and to prolong opioid use rather than facilitate recovery. Many individuals remain dependent for decades, experiencing difficulties in achieving abstinence due to severe withdrawal symptoms and long-term neurological changes caused by sustained opioid use.

3. Effectiveness in Reducing Illicit Drug Use – While methadone is promoted as a harm reduction strategy, findings suggest it does not significantly reduce illicit drug use in the long term, with many users continuing to inject heroin and other substances alongside methadone treatment.

4. Impact on Public Health and HIV/HCV Transmission – Contrary to some claims, studies indicate that methadone has a negligible effect on preventing the transmission of blood-borne diseases like HIV and hepatitis C. Research suggests that education, awareness campaigns, and access to ancillary medical, psychological, and social services are more effective at reducing risky behaviours than OAT programs.

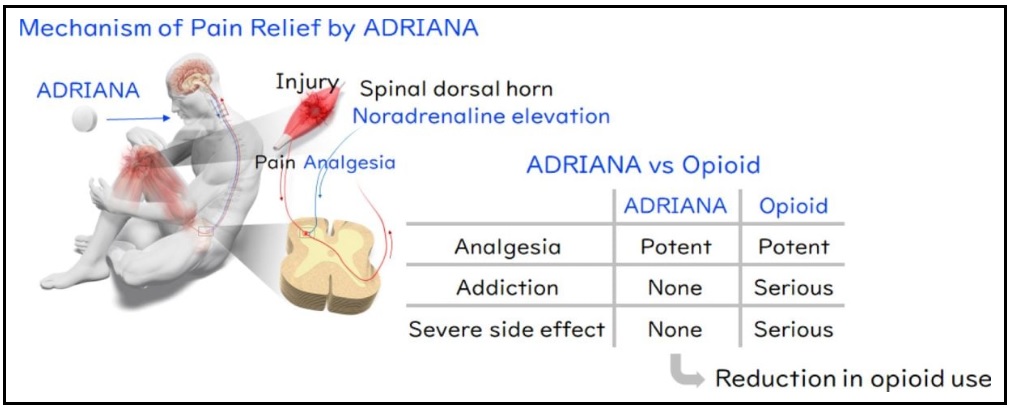

5. Comparison with Naltrexone – Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, is shown to be a safer alternative with better long-term outcomes. Studies demonstrate that long-acting naltrexone implants significantly reduce opioid use, have lower relapse rates, and allow individuals to regain normal cognitive and social functioning without ongoing opioid dependency.

6. Social and Psychological Consequences – Methadone treatment often leads to stigma and social limitations, with patients reporting dissatisfaction due to daily dosing requirements, the inability to travel freely, and a diminished quality of life. Many individuals perceive methadone as a “liquid handcuff” that prolongs addiction rather than offering a pathway to recovery.

7. Policy Implications and Recommendations – The paper suggests a re-evaluation of harm reduction policies that heavily rely on methadone. Instead, it advocates for greater accessibility to naltrexone-based treatments and comprehensive support services that focus on achieving full recovery rather than maintaining opioid dependence.

Conclusion:

While methadone remains a widely used treatment for opioid dependency, this review raises significant concerns regarding its long-term efficacy, safety, and impact on individuals’ lives. The findings suggest that long-acting naltrexone devices present a more viable alternative for those seeking complete abstinence, and public health strategies should shift towards supporting opioid-dependent individuals in achieving full recovery from addiction, restoration of cognitive function, and resumption of more productive activities rather than indefinite substitution therapy.

1. Introduction

This paper critically examines the effectiveness, safety, and long-term outcomes of opioid agonist treatments (OAT), particularly methadone, compared to opioid antagonists like naltrexone, in managing opioid dependency. The study reviews a vast body of research, including randomized controlled trials and cohort studies, highlighting key concerns regarding mortality, relapse rates, health effects, and the social implications of long-term OAT use. This monologue is organised as follows: Section 2 provides a review of the relevant literature, focusing on the effectiveness of Opioid Agonist Treatment (OAT), including retention in treatment, use of opioids and other drugs, injection of drugs, sharing of injection equipment, morbidity, and mortality while in treatment while not in treatment. In Section 3, I detail the research that relates to the effectiveness of OAT in the prevention of the transmission of blood-borne viruses. Section 4 presents the results of the research on long-term MMT, recent changes in the demographics of OUD people, and the structural brain changes from chronic drug use, while Section 5 reports on the evidence examining the effectiveness of slow-release naltrexone implants, and Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the research findings for methadone and naltrexone and makes recommendations, based on the evidence.

2. The Effectiveness of Opioid Agonist Treatment (OAT)

Good evidence for the effectiveness of methadone is scant, consisting of poorly designed and implemented, mainly observational studies and very few quality, long-term RCT studies that are free of serious bias, with a history of ad-hoc-cherry-picking of dependent variables that look promising. It is also marked by extravagant claims based on wishful thinking and unsubstantiated assumptions, or at best, misleading associations (e.g. needle sharing and coincidental HIV transmission among IUDs and the claim that methadone was a critical component and cause of low infection rates, when research demonstrated that it was not protective of HIV transmission) (Ameijden, 1885) and the realisation of the harm that it causes only when the harm has already been done (e.g. the mortality rates of six times more on leaving MMT, compared to when people are in MMT (Caplehorn and Drummer, 1999; Santo, et al. 1995), and failure to safely and responsibly implement the program and rarely making any admission of these failings (e.g. that ancillary services were essential for the effective and responsible use of methadone and the implementation of dosing with virtually none of these services being made available to the patients, including medical examinations (Ward, 1995)) and in all probability concealment of the real level of harm (e.g. as revealed by the hugely disproportional number of fatalities caused by unscrutinised prescribing of methadone for chronic pain relief in the early 1990s in the US) (CNC, 2012). Most heinous is the irrational rejection and offhand denial of the solid evidence for the effectiveness of naltrexone in the effective treatment of OUD.

In this monologue, the evidence to support this thesis will be methodically documented and rigorously defended.

It is important to set the stage by making explicit the tragic consequences of opioid use disorder OUD and the urgent need to find a solution to stem the tide of death and destruction that is causing in our communities. Illicit opioid use, especially heroin injection, causes significant personal and public health problems in many countries across the globe (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2008). Apart from the burden on users, their families and the broader community, opioid dependence increases the risk of premature mortality (Darke et al., 2006). This elevated risk is concentrated in several causes of death: accidental drug overdose, suicide, trauma (e.g. motor vehicle accidents, homicide, or other injuries), the spread of HCV infections and risky behaviour that facilitates the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (Degenhardt et al., 2004, Degenhardt et al., 2006, Darke et al., 2006).

According to Santo and colleagues (2021), researchers claimed that multiple randomised controlled trials and observational studies had found that “methadone treatment decreases illicit opioid use and other drug use, improves social functioning, decreases offending behaviour, and improves health” claims that had been made by earlier researchers (Ward et al., 1998, Mattick et al., 2003). All these outcomes it was claimed, were due to the circumstances surrounding attending dosing facilities, such as having to spend less time finding and pursuing illicit opioids without reducing their dependence on opioids, the use of other illicit drugs, or the risks involved. It is noteworthy that these researchers do not associate OAT (methadone or buprenorphine) with any reduction in mortality or that it was protective against HIV or HCV, which had been the most influential claims that led to many countries adopting OAT programs.

However, early reports of research into the effectiveness and safety of methadone as a substitute treatment for opioid dependency raised concerns that were confirmed by later research, which initiated the search for a safer agonist substitute than methadone. In 1998, Ward (1995) stated that: “Opioid pharmacotherapy is not without its own risks” and that it does not “completely remove the excess mortality risks that opioid-dependent persons are known to face” (Darke et al., 2006). Moreover, studies had shown “high mortality during the period of induction onto methadone “ (Caplehorn, 1998, Buster et al., 2002). Later research confirmed that the period at induction onto methadone and after cessation of methadone dosing carried elevated mortality risks (Caplehorn and Drummer, 1999; Buster et al., 2002; Brugal et al., 2005).

”

In a report of this more recent research conducted by Santo and colleagues (2021), the authors collected and analysed data on all-cause or cause-specific mortality among people with opioid dependence while receiving and not receiving (OAT) from all observational studies and from randomized clinical trials (RCTs). In all. 15 RCTs, comprising 3852 participants, and 36 primary cohort studies, of 749,634 participants, were analysed.

The authors introduced their paper by proclaiming that “methadone and buprenorphine were classified by the World Health Organization as essential medicines for opioid agonist treatment (OAT) for opioid dependence and that there is “robust evidence from a recent systematic review that during OAT, overdose and all-cause mortality are reduced among people with opioid dependence”, citing a published paper of Sordo, et al.(2017), which concluded that “people who cease OAT are at the highest risk of all-cause and overdose mortality in the first 4 weeks after treatment cessation and that risk of mortality is elevated in the first 4 weeks of OAT compared with the remainder of time of receiving OAT”. This paper did not address the broader issue of “overdose and all-cause mortality” being “reduced among people with opioid dependence”, but only reviewed the deaths of people with Opiate Use Disorder (OUD), while they were in OAT and during the period when they had recently commenced or ceased the treatment.

In their review, Santo and colleagues (2021) aimed to (1) examine and compare all-cause and cause-specific crude mortality rates (CMRs) during and out of OAT, for both randomised clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies; (2) examine these rates according to specific periods during and after treatment; (3) examine and compare all-cause and cause-specific CMRs for OAT provided during incarceration, after release from incarceration while receiving OAT, and according to the amount of time receiving and not receiving OAT after release from incarceration; and (4) to examine the association between risk of mortality during and out of OAT by participant and treatment characteristics. They claimed that this kind of systematic review of the evidence related to the use of OAT and other causes of death had not been done before.

They concluded that among the cohort studies, the rate of all-cause mortality during OAT was more than half of the rate seen among those who had left OAT. They found that 45 deaths in total were reported across Randomised Clinical Trials (RCTs) and that 7 of 15 RCTs (47%) reported no deaths. They concluded that there was no significant difference in all-cause mortality for patients allocated to OAT compared with comparison groups and that three of 15 RCTs (20%) evaluated the administration of OAT to people with OUD who were incarcerated where no deaths were reported.

They went on to report that in the “first 4 weeks of methadone treatment, rates of all-cause mortality and drug-related adverse events were almost double the rates during the remainder of OAT. Further, all-cause mortality was 6 times higher in the 4 weeks after OAT cessation (RR, 6.01; 95% CI, 4.32-8.36), remaining double the rate for the remainder of the time they were not receiving OAT.” The researchers concluded that the results suggested that “RCTs of OAT were underpowered to examine mortality risk” and that “there was no significant association between OAT and mortality risk in the pooled community RCTs. They found that viral hepatitis mortality was higher among those who received OAT in 7 studies. they also found that people with opioid dependence were at substantially lower risk of suicide, cancer, drug-related, alcohol-related, and cardiovascular-related mortality during OAT compared with time while not receiving OAT and while they had hypothesised a relationship between OAT and mortality risk due to injection-related injuries and diseases, such as bacterial infections, “no such relationship was identified.”

However, depending on which comorbidities were considered, researchers reported divergent findings. For example, in one study, Nosyk et al. (2009), found retention was higher among people with greater comorbidity (measured as the number of chronic diseases), while two other studies both suggested that there was no association between HIV or HCV status and retention in OAT (Kimber, 2010; Gisev, 2015)

An Australian study suggested that depression and other substance use disorders were associated with increased retention in OAT, whereas psychosis was associated with reduced retention. Moreover, cohort studies that had adjusted for comorbidity did not find changes in the estimated mortality risk by time during and out of OAT (Degenhardt et al. 2009).

Despite the reported findings, they concluded that the results of the systematic review meta-analysis, showed that OAT was “an important intervention for people with opioid dependence, with the capacity to reduce multiple causes of death.” They suggested that despite this positive association, few people with OUD stay in OAT for very long, and participation remains limited in the US and globally, perhaps due to the low uptake of OAT and a perception among OUDs that there were more negative aspects to OAT than there were benefits.

As indicated above, the study cited Sordo, et al.(2017), who did not provide this “robust” evidence of the benefits of OAT or that, overdose and all-cause mortality were reduced among people with opioid dependence., but compared “all-cause deaths” for people retained on methadone and buprenorphine and those who had recently left treatment, and concluded that “Retention in methadone and buprenorphine treatment is associated with substantial reductions in the risk for all-cause and overdose mortality in people dependent on opioids.”, compared to those who leave treatment and for the first two weeks after they enter treatment. This infers that mortality is higher for those who are retained on methadone and is even higher when people first commence OAT and when they leave an OAT program than opiate-dependent people who had never entered treatment. It does not say otherwise, as it does not include people who never entered OAT programs and who continued to use other opioids, whether prescribed or otherwise, or those who had managed to detoxify and achieve abstinence from all drugs, including methadone. They then concluded that “The induction phase onto methadone treatment and the time immediately after leaving treatment with both drugs are periods of particularly increased mortality risk, which should be dealt with by both public health and clinical strategies to mitigate such risk and base their predicted reduction in deaths on improved strategies to keep people dependent on the substitute opioids for longer periods.” They conclude that “further research must be conducted to properly account for potential confounding and selection bias in comparisons of mortality risk between opioid substitution treatments, as well as throughout periods in and out of each treatment.” (Sordo, et al., 2017)

It suggests that those who are inducted into OATs are more likely to die than if they had never been dosed with methadone. It becomes apparent that high-dose methadone leaves the user at high risk of unintentional overdose and death when they use other drugs that suppress respiration due to the synergistic effect of these drugs. It is well documented that the risk of overdose is greatly increased when opioids, including methadone, are used in combination with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines (Degenhardt and Hall 2012).

Further to this, a study by the CDC in 2012 in the US, found that “by 2009, methadone accounted for nearly one-third of all opioid-related deaths, even though it represented only 2% of opioid prescriptions.” It was thought that methadone’s long half-life led to overdose deaths. The report also noted that “methadone accounted for 39.8% of single-drug opioids prescribed for pain relief (OPR) deaths, highlighting its significant role in overdose fatalities when used alone.” This suggests that while the number of prescriptions was significantly lower compared to other opioids prescribed for pain relief, the risk was higher as the overdose death rate for methadone was significantly greater than that for other OPRs for multidrug and single-drug deaths. (CDC, 2012). Although the figures for mortality for OUD people undergoing MMT are not made available, it strongly suggests that the risk of mortality associated with the use of methadone for OUD people is far greater than advocates for MMT are willing to admit.

Opiate use is inherently dangerous, with death rates among groups not in treatment ranging from 1.6 to 8.4% with, on average, over 29 studies showing a death rate of 5.1% (Caplehorn et al., 1996). Moreover, patients in methadone maintenance show death rates of between 0.76% and 4.4%. Patients who had been discharged from methadone treatment show death rates between 1.65 and 8.4% averaging 4.9% from six studies (Caplehorn et al., 1996). However, diverted methadone has been implicated in higher death rates. In Scotland 79% of drug-related deaths were found to involve methadone, either alone or in combination with other drugs (Ling, Huber, & Rawson, 2001)

It may also suggest that ongoing dysregulation and discomfort while taking methadone and withdrawal symptoms both when leaving MMT and following a missed dose, and the inability of those in MMT to achieve abstinence are the reasons that people leave OAT programs as they find it impossible to succeed given the severity and prolonged and severe withdrawal symptoms This seems to be directly related to the unacceptable rise in deaths, when these people resume injecting other, more potent opioids and other CNS depressant drugs. In light of this, it is inconceivable that these ‘experts’ would not consider the preferred option of their patients becoming abstinent and meeting the needs of their patients based on the evidence of the efficacy of using extended-release naltrexone to facilitate this course of action.

In defence of their assertion as to the proven effectiveness of reducing illicit opiate use and the other claimed benefits of OAT, Sordo and colleagues (2017) referenced the Cochrane reviews of the evidence presented by Mattick and colleagues (2003 and 2009) and Larney and colleagues (2014). The authors reported eleven studies that met the criteria for inclusion in this review, all were randomised clinical trials, and two were double-blind. There were a total number of 1969 participants. The sequence generation was inadequate in one study, adequate in five studies and unclear in the remaining studies. The allocation of concealment was adequate in three studies and unclear in the remaining studies. Methadone appeared statistically significantly more effective than non-pharmacological approaches in retaining patients in treatment and in the suppression of heroin use as measured by self report and urine/hair analysis (6 RCTs, RR = 0.66 95% CI 0.56-0.78), but not statistically different in criminal activity (3 RCTs, RR=0.39; 95%CI: 0.12-1.25) or mortality (4 RCTs, RR=0.48; 95%CI: 0.10-2.39). The 2009 paper found that there was a significant improvement in reduced injecting and retention in treatment, however, there was no significant difference in criminality and mortality between those on methadone maintenance medication and those not receiving treatment, which contradicted the findings of Sordo, although Mattick’s review included the broader group of those with OUD including those who had never been in OAT. The inference is that OAT did not significantly decrease mortality or criminality among OUDs. In the Cochrane Review of 2014, Larney and colleagues found that a moderate dose of “buprenorphine did not suppress illicit opioid use measured by urinalysis and was no better than placebo” and that there was high-quality evidence that buprenorphine, “was less effective than methadone in retaining participants” and “For those retained in treatment, no difference was observed in suppression of opioid use as measured by urinalysis or self-report.”. Again, these studies did not provide evidence of the effectiveness of OAT programs, either by dosing people on methadone or buprenorphine, but merely compared the two pharmacotherapies with both linked to unacceptable risk.

In the Sordo (2017) paper, they made the claim that OST has been shown to reduce mortality, and they cite a paper published in 2009, written by Degenhardt et al., as evidence of this claim. However, this paper does not show that this is the case as the results were reported as:

“ Mortality among 42,676 people entering opioid pharmacotherapy (methadone) was elevated compared to age and sex peers, where drug overdose and trauma were the major contributors. Mortality was higher out of treatment, particularly during the first weeks, and it was elevated during induction onto methadone but not buprenorphine, a partial agonist/antagonist. Mortality during these risky periods changed across time and treatment episodes. Overall, mortality was similarly reduced” (compared to those who had withdrawn from the treatment) “whether patients were receiving methadone or buprenorphine”. It was estimated that the program produced a 29% reduction in mortality across the entire cohort”. That is, for those who were in OAT or had recently commenced or ceased OAT.

They concluded that:

“Mortality among treatment-seeking opioid-dependent persons is dynamic across time, patient, and treatment variables. The comparative reduction in mortality during buprenorphine induction may be offset by the increased risk of longer out-of-treatment time periods. Despite periods of elevated risk, this large-scale provision of pharmacotherapy is estimated to have resulted in significant reductions in mortality” That is, only while people are retained in treatment,

However, Mattick et al., in a paper published in 2003) admitted that: “The need for supervised daily dosing of methadone in a defined treatment setting, and evidence of increased overdose death on induction into MMT “ (not to mention the even higher mortality among those leaving OAT programs), “ prompted the search for alternative pharmacological treatment options. As a partial agonist, buprenorphine produces less depression of respiration and consciousness than methadone, thereby reducing the overdose risk. They state that buprenorphine is longer acting than methadone, allowing for less than daily dosing, although it has been found not to be effective in retaining people in treatment, as it is not effective in suppressing opioid craving and is not favoured by injecting drug users (IDUs) as it blocks the effect of opiates and it is not without risks when people inject it,” (Mattick, 2014) and it was reported “buprenorphine did not suppress illicit opioid use measured by urinalysis and is no better than placebo and that there was high-quality evidence that buprenorphine”, “was less effective than methadone in retaining participants”. This statement is very telling as it was earlier declared that a substitute for methadone needed to be found because of the poor outcomes of MMT and that buprenorphine seemed superior (Mattick et al., in a paper published in 2003). So, it seems that there were doubts, even alarm, about the effectiveness and safety of methadone some 15 years before given the unacceptable rate of mortality upon induction onto methadone and for a period following cessation of the treatment (Sordo 2017; Degenhardt et al., 2009).

To further investigate the efficacy of OAT, Degenhardt and colleagues (2009) conducted a large-scale demographic study of OUDs entering OAT over a period of.10 years in NSW.

The stated aims of the study were to:

• “(i) Estimate overall mortality for all persons entering opioid pharmacotherapy between 1985 and 2006, by demographic and treatment variables;

• (ii) Examine whether demographic or treatment variables were related to mortality levels during and following cessation of treatment;

• (iii) Estimate mortality risk, according to specific causes of death, during time within treatment and following cessation of treatment;

• (iv) Estimate the number of lives that may have been saved by the provision of methadone and buprenorphine in NSW over this period (ie. Within treatment and following cessation of treatment)

• (v) That is, to consider the estimated lives saved from the improved clinical delivery of these treatments” by keeping people on methadone for longer periods (indefinitely) therefore reducing deaths when they leave and re-enter treatment.

And further:

“Mortality among opioid-dependent people entering opioid pharmacotherapy is elevated compared to age and sex peers, with overdose, external causes and suicide the major contributors. This elevated mortality is higher when out of treatment (i.e., treatment reduces mortality only while people are retained in treatment), and it is particularly elevated during the first weeks out of treatment. The elevation in mortality varied in ways that probably reflect heroin availability and use. Mortality was highest during induction onto methadone”. (Degenhardt, 2009).

Nowhere in this paper does it state that OAT programs reduced mortality among opioid-dependent people who have not entered treatment, nor does it offer any evidence to support this contention.

Moreover, methadone is associated with continued injection of heroin and other drugs, as the overall median duration of injecting is longer for those who start methadone compared to those who don’t. For those who do not start methadone treatment, the median time of injecting is 5 years (with nearly 30% ceasing within a year) compared to a prolongation of opioid use and injecting for up towards 40 years (albeit at a reduced frequency) or more for those who continue with opioid substitution treatment (Kimber, Copeland, Hickman, Macleod, McKensie, De Angelis & Robertson, 2010). This means that if the time in agonist treatment is up to 8 times as long, the harm that is associated with injecting drugs, will inevitably result in an overall increase in mortality and morbidity.

It must be asked why Sando did not simply refer to some of the earlier studies that were enthusiastically referred to as robustly and overwhelmingly validating the efficacy of OAT and had convinced many that methadone was effective and achieved reductions in heroin use and other drug use, unsafe injecting, criminal activities, social dysfunction, and mortality, and prevention of BBV transmission. The reason appears to be that these studies were flawed and did not provide convincing evidence of the effectiveness of methadone among the population of OUDs attending community-based methadone dispensing facilities or in the prison system.

Many of the papers justifying methadone were conducted over only 6-12 months with some as short as a few weeks, often with small samples (often only 7 or 8 subjects in each arm) and with using non-representative populations. A breakdown of some early studies indicates several problems that make these claims doubtful.

The Dole et al. (1969) study that was considered a landmark study confirming the benefits of methadone had a duration of 12 months and looked at two groups: MM (16) vs. Control (16), and reported on daily heroin use. With an odds ratio of 0.01 (0.0–0.2), it tended to support the contention that methadone was effective in reducing heroin injecting. While it is expected that there would be a decline in heroin use, compared to the control group, who inevitably would continue to use heroin, and given its addictive properties, the study did not report on other variables that were considered to be vitally important, such as mortality, the use of other drugs, the dropout rates, and the movement in and out of the program, changes in health status and social functioning, among others, as they may not have been tested for or they did not reach significant levels and were not reported. Moreover, the very small number of subjects that were not randomly allocated to treatment levels raises some doubts about the robustness of these results.

A similar outcome was reported by Gunne & Gronbladh (1981), with a study duration of 24 months. The study compared MM (17) to a control group (17) with an odds ratio of 62.4 (8.0–487.9). Again, it seems that the reported outcomes that more were retained in MM treatment were expected, although the width of the CI (e.g., for treatment retention and discontinuation of illicit drug use) indicated variability, likely due to the small sample size and/or the heterogeneity in the study design, and that the subjects were not randomly allocated makes the results unreliable. Again, they did not report on other variables that are of vital interest perhaps because they were not significantly different.

However, several studies with larger subject numbers, were completed: Newman & Whitehill (1976), with a study of duration 36 months MM (50) vs. Placebo (50) found a reduction in imprisonment for those on OAT (0dds ratio 0.02; CI 0.0–0.4); Vanichseni et al. (1992) in a study with a duration of 45 days compared MM (120) vs. Methadone detoxification (120) (Interim), and found that numbers that were discharged for heroin use were different between the two groups with an odds ratio 0.3 (0.1–0.9); Yancovitz et al. (1992) showed a similar pattern with a trial period duration of one month comparing MM (121) vs. Control (118), found that discontinuing regular illicit drug use favoured the MM group with an odds ratio of 38.4 with a wide CI of 4.0–373.1; Strain et al. (1993) reported on four outcomes of a study with a duration of 20 weeks that compared MM 50 mg (84) vs. Placebo (81) to test the odds of each group testing positive to morphine >50% of the time, completing 45 days in treatment, returning a positive urine test for morphine and retention in MMT at 20 Weeks with each trial favouring the MM group, with odds ratios of 4 (CI 0.2–0.6), 6.1 (3.4–10.6), 0.3 (0.2–0.5), and 4.1 (2.1–8.2), respectively. Apart from the study by Newman & Whitehill (1976), which included 50 subjects in each comparison group and had a duration of 36 months, the duration of these other studies was very short. Notwithstanding, this study is flawed as it chose “imprisonment,” a curious dependent variable to test, because it can relate to the commission of a crime prior to coming into MMT or during MMT and that may be unrelated to drug use. Like this, of the many variables that are touted as being positively affected by MMT, each study reported on a single and predictable variable.

The choice of the variable to be measured seems to be done ad hoc, rather than a priori. This occurs when there are no significant differences that were predicted are found, such as reduced mortality or transmission of BBVs, and the researcher goes searching among the results to find a variable that did reach statistical significance when the data are reanalysed and results retested. It is also apparent that the many other variables that are meant to be impacted by MMT did not reach significance as they were not reported. It raises the possibility that many other studies that did not find any significance were never sent for publication or were rejected by the door-keeper editors of the major journals, who actively censor research that does not adhere to their views about OAT.

This research on the effectiveness of OAT is neither relevant nor informative, as it doesn’t touch on the important issues, such as mortality, morbidity, continued injecting of opioids and other drugs, reduction in risky behaviour, improved health and social outcomes, including the transmission of BBV, nor does is it sound in its methodology, design or analysis of findings, as it rarely extends over sufficient time to be useful as many people cycle in and out of treatment or tend to stay on methadone for 20 to 40 years. Even though, death represents the more relevant effect of abuse and the more reliable outcome measurable in population studies, mortality is rarely reported in RCTs of treatment of opioid dependence and is seldom considered to assess the efficacy of treatments. The issue of association between intermediate and surrogate indicators and the actual outcome of interest (i.e., quality and duration of life) seems to be extremely relevant in the interpretation and generalization of the results of these studies and should be the subject of high-quality long-term RCT studies. The high rates of mortality among people leaving MMT, and large numbers cycle in and out of treatment, and disproportionate mortality among people prescribed methadone for chronic pain relief should have been predictable had these precautionary studies been done (Amato, 2005).

An exception was a prospective open cohort study, conducted over a period of 27 years. Kimber et al. (2010) examined survival and long-term cessation of injecting in a cohort of drug users and assessed the influence of opiate substitution treatment on these outcomes. 794 patients with a history of injecting drug use presented between 1980 and 2007; 655 (82%) were followed up, and (85%) had received OAT. Results showed that of the total number of those in the cohort, 277 participants achieved long-term cessation (5 years or more) of injecting, and 228 died. Half of the survivors had poor health-related quality of life. The median duration from first injection to death was 24 years for participants with HIV and 41 years for those without HIV. For each additional year of opiate substitution treatment, the hazard of death before long-term cessation fell by 13% (95% confidence interval 17% to 9%) after adjustment for HIV, sex, calendar period, age at first injection, and history of prison and overdose. Exposure to opiate substitution-agonist treatment (OAT) was inversely related to the chances of achieving long-term cessation of injecting. They concluded that although survival benefits increased with cumulative exposure to treatment, the “treatment does not reduce the overall duration of injecting” and, therefore, did not have an impact on the transmission of BBV, which was declared to be a major benefit of OATs.

The study reported by Yancovitz et al., (1991) that was mentioned earlier, comprised 149 subjects who were randomly assigned to a treatment group and to a control group of 152 not on OAT at an interim methadone maintenance clinic. The treatment group was on a maintenance dosage of 80 mg/day. One-month urinalysis follow-up data of 129 subjects originally assigned to the treatment group and 121 assigned to the control group showed a significant reduction in heroin use in the treatment group with no change in the control group. A higher percentage of the treatment group were in treatment at the 16-month follow-up. The researchers claimed that the limited services interim methadone maintenance group reduced heroin use while waiting for entry into a comprehensive treatment program, which resulted in an increased number entering treatment compared to the group that received no treatment. This was not only very short-term (one month of drug testing), but it did not have any bearing on the experience of those who attended unsupported methadone dispensing facilities over many years. Moreover, it must be asked, as they were all dependent on opioids, what was it that the control group was meant to do but to continue to use heroin while they waited to join the MMT program? While it was no surprise that those receiving methadone were spared the inconvenience of having to source heroin each day, it seemed that, in any case, many did. Further to that, there appeared to be no other benefits of being dosed on methadone that were worth reporting (Yancovitz et al., 1991).

In a 1981 study by Gunne and Grönbladh, the sample size was notably small, with only 34 participants divided equally between the methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) group and the control group. Such limited sample sizes can significantly impact the statistical power of a study, making it difficult to detect true effects. Additionally, small samples may not accurately represent the broader population, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, while the study reported positive outcomes for the MMT group, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the potential limitations imposed by the small sample size. Again there were no other significant findings that were worth reporting despite their importance in evaluating the efficacy of MMT. (Suresh & Chandrashekara, 2012)

In 2007, Kinlock and colleagues conducted a randomized clinical trial examining the impact of methadone maintenance initiated in prison on post-release outcomes. The study involved 204 incarcerated males with pre-incarceration heroin dependence, who were assigned to one of three groups: counselling only, counselling with transfer to methadone maintenance upon release, and counselling with methadone maintenance initiated in prison and continued post-release. Findings at 12 months post-release indicated that participants who began methadone maintenance in prison had higher treatment retention and lower rates of opioid use compared to the other groups.

Regarding the relevance of the 2007 study by Kinlock and colleagues, which involved men with pre-incarceration heroin dependence, the findings demonstrated that initiating methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) in prison led to higher treatment retention and lower rates of opioid use post-release compared to other groups. However, generalising these results to populations beyond incarcerated individuals would not be valid. The unique environment of incarceration, along with factors such as structured daily routines, limited access to illicit substances, and diversion of methadone, were likely to influence treatment outcomes differently than in non-incarcerated settings. In conclusion, the authors say, “Methadone maintenance initiated prior to or immediately after release from prison appears to have a beneficial short-term impact on community treatment entry and heroin use.

Therefore, while the study provided some insights into the impact of initiating MMT. during incarceration, further research was necessary to determine if these findings were applicable to prisoner populations and if they persist in being dosed, let alone other populations, such as individuals undergoing long-term, community-based treatment programs. It is also apparent that prisoners who leave jail while being dosed on methadone are at elevated risk of overdosing and death, especially when they find it difficult to find a dosing facility once released and withdrawal symptoms become intolerable.

A later meta-analysis of opioid-related mortality by Gahji and colleagues in 2019 tended to confirm this heightened risk of overdose, when they found that in a total of 32 cohort studies (representing 150 235 participants, 805 423.6 person-years, and 9112 deaths) that met eligibility criteria, crude mortality rates were substantially higher among methadone cohorts than buprenorphine cohorts. Relative risk reduction was substantially higher with methadone relative to buprenorphine when time in-treatment was compared to time out-of-treatment. This statement means that when comparing the effectiveness of methadone versus buprenorphine in reducing a specific risk (likely overdose or relapse), methadone appeared to provide a greater reduction in risk, but only when considering the time that patients were actively in treatment versus the time they were out of treatment.

This suggests that while people are actively in treatment, methadone provides a stronger protective effect against overdose, death, or other risks compared to buprenorphine.

It also means that looking at overall death rates, more deaths occurred in methadone patients compared to buprenorphine patients.

To make sense of this information, it is necessary to understand the mechanism that leads to methadone deaths being 6 times higher during the period after leaving an MMT program, that results in over 30% of the deaths of those using prescription opioids when only 2% of the opioid pain relief prescriptions are for methadone and 79% of the overdose deaths among a group of hardened long-term opioid addicts and leads to an unacceptable death rate among those on MMT.

Users can develop tolerance to methadone, like other opioids. Tolerance occurs when the body adapts to the drug’s effects over time, requiring higher doses to achieve the same therapeutic or subjective effects. However, tolerance develops unevenly across different effects of methadone, and some effects may persist even as others diminish. Even after withdrawal symptoms begin, significant levels of methadone remain in the body due to its long half-life (24–36 hours). This creates a dangerous scenario where a person experiencing withdrawal might take additional opioids (e.g., heroin, fentanyl, or oxycodone) to relieve symptoms, inadvertently risking overdose from the combined effects of residual methadone and the new opioid. Methadone and other opioids both suppress breathing. Even partial residual methadone can synergize with a new opioid dose, overwhelming the respiratory system. Tolerance to respiratory depression is incomplete, so combining opioids can lead to a fatal overdose even in tolerant individuals (SAMHSA).

SAMHSA (2012) warns that relapse during methadone withdrawal is a high-risk period for overdose due to fluctuating tolerance and residual methadone and CDC Data shows that individuals discontinuing methadone or other opioids face a 5–10× higher overdose risk in the first 2 weeks of withdrawal.

After 1–3 days, withdrawal begins, but methadone levels are still substantial. Adding another opioid risks immediate overdose, and after 4–14 days, methadone levels decline further, but tolerance may drop rapidly. Relapse doses that were once “safe” can now be fatal. {SAMSHA, 2012)

Moreover, it seems that those who have gone into MMT hoping for substantial benefits, as promised by the advocates, have not experienced an improvement in health or social functioning. Rather, they are subject to numerous negative effects as they develop tolerance to methadone. These include tolerance to methadone’s pain-relieving effects can develop, particularly in individuals using it long-term for chronic pain. Higher doses may be needed over time to maintain efficacy. Tolerance to the euphoric and sedative effects develops relatively quickly. It heightens overdose risk if users resort to other CNS depressants to get pain relief and who want to experience the euphoria that initially lead to becoming dependent on opioids. It also includes partial tolerance to respiratory depression however, this tolerance is incomplete, and overdose remains possible if methadone is combined with other depressants (e.g., benzodiazepines, alcohol). However, other effects of methadone are not diminished over time, such as little to no tolerance develops to methadone’s constipating effects, chronic use can suppress testosterone, estrogen, and cortisol production, leading to issues like low libido, fatigue, or osteoporosis as tolerance to these effects is minimal. These complications can become debilitating and users become desperate to detox and be free of this drug and dropping out of MMT and exposing themselves to high risks of overdose.

As reported by Mattick and colleagues, “a consistent finding in the studies of methadone-assisted heroin detoxification is the high rates of relapse to heroin use following cessation of methadone doses” (Mattick et al., 2009a, p 65) with a high risk of overdose and death. Despite this admission, the same authors state that “Methadone assisted withdrawal has shown to be safe, effective and acceptable” (Mattick, et al., 2009a, p85)

.

It seems that users are aware of these aspects of being on MMT for long periods and are not choosing to enter these programs. Further to this, it is likely that despite the continued endorsement of the effectiveness and safety of MMT in the face of overwhelming evidence that says otherwise, health practitioners are not keen to refer opioid-dependent people to MMT, particularly in view of the changing demographics of this group from predominantly heroin users to chronic pain patients who become addicted to prescription opioids. This accounts for the lack of expansion of the number of new people entering MMT.

3. The Effectiveness of OAT in Reducing Transmission of HIV.

The move towards a harm reduction approach was given impetus by what was discovered about the association between injecting drug use and the transmission of blood-borne infections such as HIV and hepatitis B and C. (NDARC, 1995; Ward 1995)

By the early 1980s, reviewers of short-term uncontrolled-observation studies supporting the use of OAT claimed that there was sufficient evidence “to conclude that methadone maintenance treatment led to substantial reductions in heroin use, crime, and opioid-related deaths, and that it was highly likely that methadone maintenance would also contribute significantly to preventing the spread of HIV among injecting opioid users”, and were used to endorse methadone maintenance as part of shift toward Harm Reduction of NCADA and the subsequent expansion that took place in methadone services around Australia. In 1985, there were some 750 people on MMT programs in NSW, and by 1995, this had increased nine-fold to over 6,750 participants. An important aim of research over the decade before 1995 was to determine whether methadone maintenance contributed to the prevention of the spread of HIV among injecting drug users. They thought that there were two ways in which this might be established: from studies that examined whether being in methadone maintenance was protective against HIV infection, and by those which examined the extent to which methadone maintenance reduced the likelihood of needle sharing among its recipients. Such was the conviction that methadone was the key to the prevention of the harm associated with opioid use that the contribution of ancillary services to successful methadone maintenance treatment was subject to debate as it was unclear what proportion of clients would want and if they would make use of such services, and what kinds of problems might be addressed by them. In any case, there was a reduction in the types and numbers of services that were provided at methadone clinics due to the rapid expansion of services delivered by the private sector. (Ward, 1995). However, research that was available at the time, made it clear that the provision of ancillary services such as education, awareness campaigns, exposure to primary health care services, and the provision of condoms for those with OUD, were the major factors in changing behaviour that led to the comparatively low rates of HIV transmission in Australia. (Wodak and McLeod. 2008;Ward, 1995; Ameijden, 1994).

A series of studies conducted over 6 years, examined methadone programs in Amsterdam and found that they “were not protective against HIV infection, not associated with significant reductions in injection-related risk behaviour, and not protective in terms of preventing the transition from non-injecting to injecting opiate use.” However, they reported that the provision of advisory/counselling services, public awareness campaigns, education about risk factors and HIV testing played a decisive role in achieving some positive outcomes (Ameijden, 1994).

Another report found that there was a lack of convincing evidence that attending exchange programs or receiving methadone treatments had a beneficial effect on the HlV prevalence, HIV incidence, or current sharing of equipment. They also found indications that voluntary HIV Antibody testing and/or counselling reduced high-risk behaviour (van Ameijden, van den Hoek, et al.,1994). In an earlier paper published in 1992, the authors studied a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative injecting drug users in Amsterdam and found that there was no evidence that receiving daily methadone treatments at methadone posts and obtaining new needles/syringes via the exchange program were protective.

The studies conducted and reported by Ward (1995) had as its broad purpose, “in light of the literature reviewed and recent changes to the New South Wales public methadone programs, an attempt to build upon the methodology and the findings reported by Ball and Ross in examining the relationship between aspects of treatment received and treatment outcomes and to investigate the role of factors outside of treatment (life events, social support) in predicting outcomes” (Ward, 1995). However, contrary to the evidence before him, he took the view that the reviews concerning the use of methadone as a treatment for opioid dependence had found that there was sufficient evidence to conclude that methadone maintenance treatment led to substantial reductions in heroin use, crime and opioid-related deaths, and that it is highly likely that methadone maintenance would also contribute significantly to preventing the spread of HIV among injecting opioid users. These reviews, therefore, supported the endorsement of methadone maintenance as part of NCADA and the subsequent expansion that took place in methadone services around Australia.

Alex Wodak, a leading figure in the adoption and implementation of harm reduction, claimed in 2008 that the “scientific debate about harm reduction is now over: harm reduction has been shown convincingly to be effective in reducing HIV, and to be safe and cost-effective. (Wodak & McLeod., 2008)

He was happy to concede that “Enduring abstinence is, after all, the ultimate way to minimise harm”. It is well known that abstinence can facilitate a reasonable quality of life by not being tied to MMT and to a never-ending regime of drug dependence that prolongs the harm associated with it, while being hopelessly addicted to a lethal drug and condemned to live as a second-class citizen. He goes on to proclaim that “it has been known since at least the early 1990s that HIV among IDU can be easily controlled by the early and vigorous implementation of a comprehensive harm reduction package. This package consists of education, needle syringe programs, drug treatment (meaning methadone to be dispensed daily) and the community development of drug users.” However, other researchers found that this package is often not provided (Ritter & Lintzeris, 2004), and it begs the question of whether he believes that OAT, even in conjunction with SNPs, is effective on its own. Researchers have responded with a resounding “No!” (Ward, 1995; Ameijden, 1994; Ritter & Lintzeris, 2004)

Later in this paper, Wodak maintains that “these programmes usually provide a great deal of practical education and also serve as important entry points for drug treatment and the provision of other basic services.” (Wodak & McLeod, 2008).

Indeed, it would be more beneficial if methadone treatment was supplemented by a range of ancillary counselling, welfare and health services. The reality is that these services are often not available and rarely taken up by IUDs, as it “it is expensive to operate these specialist services and methadone programs are often situated in general or primary health care settings or in pharmacies, where access to ancillary services is not provided” (Ward, 1995; Ritter & Lintzeris, 2004). Moreover, it is not obvious why this package of services needed to be coupled with OAT, as most of the changes in behaviour among homosexual men were the result of education programs about safe sexual practices, provided by government AIDS agencies and support groups, delivered in the early to mid-1980s, well before there were many people in MMT; meaning that the men who were most at risk of contracting HIV were not in MMT. The evidence indicates that (1) voluntary HIV testing and counselling led to less borrowing, lending, and reusing equipment, and (2) obtaining needles via exchange programs led to less reusing needles/syringes. However, it appeared that “nonattenders of methadone and exchange programs had reduced borrowing and lending to the same extent as attenders” (Ritter & Lintzeris, 2004; Ameijden, 1994).

It is recommended that “education of IDUs about the risks of unsafe sexual behaviour and sharing injecting equipment should be simple, explicit, peer-based and factual about behaviours associated with the risk of HIV transmission and practical ways of reducing risk.” (Ritter & Lintzeris, 2004). Moreover, if the person has a long-acting naltrexone implant and is abstinent, as association with people using illicit drugs, as occurs around OAT and NSP facilities, tends to promote risky behaviour, the impact of education is more effective and there is no need for people to be burdened by having to take methadone each day. It has been shown that education about safe sex practices has been effective in reducing the incidence of HIV infection among those who are not IUDs and those who are, and who are most at risk of contracting the disease, are men who have sex with men and young females who have unprotected sex with multiple partners. Moreover, it was found for those in OAT that it “had little effect in changing risky behaviour and that it did not affect condom use.” (Gowing et al., 2017)

Wodak goes on to say, “needle syringe programmes and opiate substitution treatment are often regarded as the hallmark of harm reduction.” However, these programs are largely irrelevant in the quest to reduce HIV transmission, as the research shows that HIV is rarely transmitted due to drug injection as HIV does not survive long outside the human body, and its ability to cause infection diminishes rapidly once exposed to environmental conditions. Studies have shown that drying HIV causes a rapid (within a few hours) 90%-99% reduction in HIV concentration. (Moore, 1993; Guy, 2008; CDC, 1987). Gay, bisexual, and other men who reported male-to-male sexual contact are the population most affected by HIV. In 2022, gay and bisexual men accounted for 67% (25,482) of the 37,981 new HIV diagnoses and 86% of those diagnosed were men. (CDC, 2023). The risk of sexual transmission of HIV between HIV-positive IDUs and their sexual partners is much lower at 0.02–005% per heterosexual sex act, while the risk during receptive anal intercourse between men can be 0·82% (95% CI 0·24–2·76%) (Degenhardt and Hall 2012) The risk of HIV infection via injection with an HIV-infected needle is about 1 in 125 injections. The prevalence of hepatitis C antibodies varies widely in IDUs, from 60% to greater than 90% prevalence. (Degenhardt and Hall 2012). It is estimated that men and women who inject drugs accounted for 4% (1,490) and 3% (1,161) of new HIV diagnoses, respectively. (CDC, 2023)

Wodak claimed that eight reviews of the evidence for needle syringe programs conducted by or carried out on behalf of US government agencies concluded that these programs were effective in reducing HIV and are unaccompanied by serious unintended negative consequences (including inadvertently increasing illicit drug use). More recent reviews commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US National Academy of Science came to the same conclusions (Wodak & McLeod., 2008) It seems that some experts thought OAT was a good idea based on the relationship between people who inject drugs (PWIDs) and HIV transmission, led to conclusions about its effectiveness in preventing HIV infection which were mistaken.

Many of these studies had recorded associations between injecting opioids and other drugs and various health-related harm (HIV and HCV). However, the determination of whether such associations are causal is more problematic. To make a causal inference, it is necessary to document an association between drug use behaviours and the adverse outcome, confirm that injecting the drug preceded the outcome, and exclude alternative explanations of the association, such as reverse causation and confounding (Suresh & Chandrashekara, 2012). Cohort studies of injecting amphetamine, cocaine, and heroin users suggested that these practices increase the risk of premature death, morbidity, and disability, mainly from drug overdose and blood-borne viruses. These studies have rarely controlled for unsafe male-to-male sexual practices, but the association between this behaviour and transmission of HIV is too large to be wholly accounted for by this confounding variable of a large proportion are IDUs; the major causes of increased mortality are plausibility and directly related to unsafe sexual behaviour among men, and to a lesser extent, women who have unsafe multiple-partner sexual contact (Degenhardt and Hall 2012).

The epidemiological study by Cornish et al. (1993) was influential in that people latched onto their findings and convinced bodies such as WHO of the benefits of OATs on preventing HIV transmission as it had shown a positive relationship between needle sharing and acquiring HIV and then others assumed that as methadone led to a reduction in injecting, then, in turn it would reduce HIV transmission. There, however, appeared to be significant problems with the study design and with the identification of confounding variables, the major one being the proportion of each group who were homosexual and engaged in unsafe sexual behaviour. The study did not randomly assign subjects to treatments, and they did not control for differences between the groups. As observational studies, including epidemiological longitudinal studies, do not establish causation primarily due to confounding variables, differences in outcomes could be due to other factors that vary between groups rather than the exposure to MMT itself. They also lack randomisation, resulting in confounders, which are variables that influence both the exposure and the outcome, making it difficult to determine whether the observed relationship is truly causal. In this study linking MMT to HIV, it is likely unsafe sex among men would be a confounder if the group who are not on MMT are more likely to be men engaged in unsafe and risky sexual behaviour. Reverse causation may also be an issue in that those who practice safe sex and who are not homosexual may be more likely to prefer methadone as they are more conscious of their health and the risks of HCV, for example, due to unsafe injecting. There are also some serious biases in this study that can be identified that can distort results. For example, as we have noted, participants in this observational study were not randomly chosen, which can lead to selection bias as it is possible that HIV-positive people were less likely to choose the MMT group as engaging in activities to acquire and inject street drugs other than heroin, mainly which has hypersexuality properties, which aligns with their lifestyle (Suresh & Chandrashekara, 2012).

The reality is that in 2022, it was estimated that IUDs accounted for 7% (2,651) of the 37,981 new HIV diagnoses. According to the research findings it was estimated that OUD people who injected opioids accounted for one in three PWIDs (37%) (AHIW, 2023), that 50% of PWIDs were in MMT and that MMT reduced injecting by 30% (Gowing et al., 2017 then it is possible that this reduced the number of transmissions by 0.126% or 48 cases over this period.

Wodak, despite the negligible effect of OAT on HIV transmission rates, concludes by saying that “Drug treatment is also critical, especially opiate substitution treatments. Methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment have been shown convincingly to reduce HIV spread “ (Wodak & McLeod, 2008), despite the evidence that suggests otherwise.

Gowing and colleagues (2017) claim that oral substitution treatment for injecting opioid users reduces drug‐related behaviours that are reputed to be a high risk for HIV transmission but has less effect on sex‐related risk behaviours. They say that “a lack of data from randomised controlled studies limited the strength of the evidence presented in this review.”

In their review, they go on to state: “Thirty‐eight studies, involving some 12,400 participants, were included. The majority were descriptive studies, or randomisation processes did not relate to the data extracted, and most studies were judged to be at high risk of bias.”

“The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Reviews is based on the evaluation of six specific methodological domains; namely, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and ‘other issues’ (Suresh & Chandrashekara, 2012).

Studies (Gowing et al., 2011) showed a statistically significant decrease in injecting behaviour (either as the proportion of participants injecting, the frequency of injecting drug use, or both) after entry into methadone treatment. The relative risk of injecting drug use at follow‐up compared to baseline ranged from 0.40 (at 12 months) and (at 24 weeks) to 0.80 at 6 month follow‐up (corresponding to reductions in relative risk of 60% and 20%, respectively) and other studies all showed significantly less injecting behaviour (either as the proportion of participants injecting, or the frequency of injecting drug use, or both for cohorts receiving OAT compared to those not receiving this treatment at the time of assessment. The relative risk of injecting for substitution treatment compared to no substitution ranged from 0.45 for to 0.87 for (corresponding to reductions in relative risk of 55% and 13%, respectively)”. The problem with these studies was that they were only short-term and did not look at the effect of MMT on HIV or HCV transmission rates and other long-term adverse health effects. People tend to stay on MMT for many years and, indeed, it is suggested that they do so indefinitely (Degenhardt et al., 2009; Kimber, 2010) and that they continue to inject drugs, which in the long-term diminishes any of the early benefits.

In other words, many of those receiving OAT were not injecting opioids and even among injectors, there was no evidence that HIV transmission was affected, rather it was speculated that a reduction in frequency of injecting drug behaviour could be interpreted as a reduction in new HIV infections among this group, however, it was said that it “had little effect in changing risky behaviour” including unsafe injecting and among other things that it did not affect condom use, which was the critical factor in reducing HIV transmission.”

According to a 6-year longitudinal study among IDUs in Amsterdam, from 1987 to the end of June 1993, a cumulative total of 2678 cases of AIDS were reported in the Netherlands (circa 15 million inhabitants). Homosexual men were the largest risk group (78%), followed by injecting drug users (9%); 93% of the cumulative AIDS cases were men. In 1992, 481 new cases were diagnosed and in 1991, there were 437 new cases. Most of the AIDS cases in the Netherlands were reported from Amsterdam (700,000 inhabitants) (van Ameijden, 1994). The research of Guy et al. (2007) confirmed these estimates when they found that by far the most frequent route of HIV exposure was male-to-male sex, accounting for 70% of diagnoses and that, in terms of HIV prevention, methadone treatment programs “were not protective against HIV infection, not associated with significant reductions in injection-related risk behaviour, and not protective in terms of preventing the transition from non-injecting to injecting opiate use.” Heterosexual contact accounted for 18% of cases, with just over half of these people born in or having a sexual partner from a high-prevalence country, or were young women who had unsafe sex with multiple partners and that transmission by injecting drugs was rare. The risk of sexual transmission of HIV between HIV-positive IDUs and their sexual partners was much lower at 0.02–005% per heterosexual sex act, while the risk during receptive anal intercourse between men can be 82% (95% CI 0·24–2·76%) (Degenhardt and Hall 2012)

These findings tend to lend weight to the results of the review by Gowing et al., in 2011, who reported that OAT programs had little effect on injecting drug rates and, more importantly, it had minimal impact on changing sexual behaviour. As, has been shown, (Guy et al, 2007, CDC, 2023; van Ameijden, 1994) HIV is almost exclusively transmitted through unsafe sex practices and reductions in HIV transmission resulted from changes in risk-taking sexual behaviour, most importantly the use of condoms, it must be concluded that “OAT was almost entirely ineffectual in reducing HIV infection rates, either directly or indirectly by altering drug injecting or unsafe sexual behaviour.”

While the rate of HIV infection remains comparatively low amongst injecting drug users in Australia (Des Jarlais, 1994; Kaldor, Elford, Wodak, Crofts & Kidd, 1993), evidence of previous hepatitis B and C infection among people who have been injecting drugs for some time suggests that the proportion of exposed individuals is very high (80-90%) (Bell, Batey, Farrell, Crewe, Cunningham & Byth, 1990a; Bell, Fernandes & Batey, 1990b; Crofts, Hopper, Bowden, Breschkin, Milner & Locarnini, 1993). Thus, if HCV infections have the same transmission characteristics as HIV, HIV cases should be much higher therefore it is difficult to account for this anomaly, apart from the probability that MMT had negligible impact on HIV infection rates and that other factors were at play.

The research of van Ameijden (1994) and Ameijden and colleagues (1994) in Amsterdam followed 616 OUD people over 6 years. Their aim was to evaluate the protective effects of MMT and NSPs and of HIV antibody testing, counselling and the provision of educational material on risky behaviour.

They reported that previous studies in Amsterdam and elsewhere (van Ameijden,1992), had shown that “HIV testing and counselling were strongly associated with significantly lower levels of risky injecting behaviour and unsafe commercial sexual behaviour and found that NSPs and OAT had an impact on injecting drug use” however, it had “minimal if any, direct relationship to HIV infection rates.” They went on to say that if the effect of a prevention program aimed at reducing risky injecting behaviour is to be evaluated, the extent to which the sexual transmission of HIV influences the prevalence and incidence of the virus among injecting drug users must also be considered.

In discussing their results, Ameijden and colleagues (1994), reported that “it appeared that nonattenders of methadone and exchange programs reduced risky injecting to the same extent as attenders.” They found that neither NSPs or OAT had any protective effect on reducing sharing of injecting equipment or on the rate of transmission of HIV. However, they found indications that voluntary HIV antibody testing and counselling/education were the factors that reduced high-risk behaviour (Ward, 1995).

Higher levels of needle sharing, with its associated risks of transmission of HCV and other blood-borne viruses, is also associated with the use of benzodiazepines by injecting drug users. A study of non-fatal heroin overdoses in Sydney revealed that 25% of individuals reported having used benzodiazepines at the time of their last overdose. Further to this Ward (1995) found that benzodiazepine misuse increased with higher doses of methadone.

It is apparent that the rate of HIV infection is comparatively low amongst injecting drug users in Australia (Ward, 1995), due to the rapid response to the threat and quick implementation of public safety awareness and education strategies, including the most important factor; the rapid increase in the use of condoms, which occurred and had a major impact on transmission rates before methadone had taken hold in Australia. However, the evidence of previous hepatitis B and C infection among people who have been injecting drugs for some time suggests that the proportion of exposed individuals is very high (80-90%) and that a different mechanism was influencing the outcomes (Ward, 1995). Despite this, HR advocates continue to state that “methadone maintenance is effective in preventing HIV infection”, but conceded that” this may not be the case for HCV as HCV is more readily transmitted than HIV” with infection rates of between 50 and 95% (Mattick, et al.,2009a, p. 123).

4. Long-Term MMT and Changes in Demographics and the Brains of OUD people.

In the paper of Larney et al., (2020), the authors analysed the need for a comprehensive policy to combat the alarming increase in the numbers of dependent people and mortality among a largely new demographic who have become addicted to extra-medical opioids.

Of the 8683 studies identified, 124 were included in this analysis. “The pooled all-cause CMR, based on 99 cohorts of 1 262 592 people, was 1.6 per 100 person-years (95% CI, 1.4-1.8 per 100 person-years).” All-cause CMR” (all-cause crude mortality rate) means that the number of people who died from any cause during the study was 1.6 deaths per 100 person-years, which means that of 1000 people followed over one year, about 16 of them would die on average.

It also found “substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99.7%). Heterogeneity was associated with the proportion of the study sample that injected opioids or was living with HIV infection or hepatitis C” as opposed to those who were addicted to oral, either prescribed or extra-medical opioids, which infers a different group of newly dependent people. The pooled all-cause SMR, based on 43 cohorts, was 10.0 (95% CI, 7.6-13.2). SMR (standardised mortality ratio, where it compares the death rate in the study group to the death rate in the general population. In this study, the SMR was 10.0., which means that the people in these groups were 10 times more likely to die than the average person in the general population. A meta-analysis of mortality in opioid users calculated a pooled standardised mortality ratio of 14·7 (95% CI 12·8–16·5) (Degenhardt and Hall 2012).

They conclude by stating that “excess mortality was observed across a range of causes, including overdose, injuries, and from infectious and noncommunicable diseases.” They further found that those in OAT thought that

• Methadone was seen as having a “low status” and was only used to medicate to avoid withdrawal

• Methadone was seen as easy to obtain

• There was a belief that methadone was used by those not in treatment in “emergencies” (i.e. for individuals who could not get heroin)

• Methadone clients were viewed as “losers” who had “given up”

• Participants viewed methadone as a dangerous drug that had worse side effects than heroin, including bone and muscle aches, sexual problems, dental problems, and weight gain–fear of long-term effects of methadone

• Participants held the belief that methadone caused unacceptable discomfort felt during detoxification

• Participants held the belief that methadone had a more severe opiate effect, including the increased risks of overdosing

• Having to go to a clinic every day to get methadone interfered with their daily routine, including time spent with family and the ability to find and maintain employment.

It turns out that most of these beliefs are borne out by those researchers who surveyed and interviewed people who were in MMT and the impact of MMT on individual’s lives who often refer to methadone as “liquid handcuffs” (Hunt et al., 1985; Ward 1995; Divine, 2010)

Alternative forms of treatment should be implemented as variations in patterns of drug initiation between countries and cultures suggest that entry into illicit drug use is dependent on social factors and drug availability, as well as characteristics of users and social settings that facilitate or deter use.

Cohorts of users seeking treatment or entering the criminal justice system are groups whose trajectory of use can differ from users who do not enter these systems. The available evidence suggests that a minority of individuals will no longer meet the criteria for dependence a year after diagnosis (Degenhardt and Hall 2012) and that for whom being coerced onto MMT is inappropriate for all the above-stated reasons.

It has been found that major social and contextual factors increase the likelihood of use are drug availability, use of tobacco and alcohol at an early age (ie, early adolescence), and social norms for the toleration of alcohol and other drug use. (Degenhardt and Hall 2012)

It has been identified there are four broad types of adverse health effects of illicit drug use, including diverted methadone, that exist: the acute toxic effects, including overdose; the acute effects of intoxication, such as accidental injury and violence; development of dependence; and adverse health effects of sustained chronic, regular use, such as chronic disease (eg, cardiovascular disease and cirrhosis), blood-borne bacterial and viral infections, and mental disorders (Degenhardt and Hall 2012).

Many studies have recorded associations between illicit drug use and various health-related harm, but the determination of whether such associations are causal is more difficult. To make a causal inference, it is necessary to document an association between drug use and the adverse outcome, confirm that drug use preceded the outcome, and exclude alternative explanations of the association, such as reverse causation and confounding (Suresh & Chandrashekara, 2012). Cohort studies of problem amphetamine, cocaine, and heroin users suggest that these drugs increase the risk of premature death, morbidity, and disability. These studies have rarely controlled for social disadvantage, but the mortality excess is too large to be wholly accounted for by this confounding; the major causes of increased mortality are plausibly and directly related to illicit drug use (Degenhardt and Hall 2012).

Moreover, the chronic use of addictive drugs leads to significant changes in brain structure and function, particularly in areas involved in reward, motivation, memory, and self-control. These changes contribute to addiction, making it difficult for users to stop despite the harmful consequences of continued use of the drug.

Brain changes from chronic drug use include:

1.‘Dysregulation of the Dopamine System. Most addictive drugs increase dopamine levels in the brain’s reward system (especially in the nucleus accumbens), reinforcing drug-seeking behaviour. Over time, the brain reduces natural dopamine production and receptor sensitivity, making it harder to experience pleasure from natural rewards (food, social interactions, etc.)” (NIDA. 2020).

2.“Impaired Prefrontal Cortex Function (Loss of Self-Control). The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and judgment, becomes less active. This leads to poor self-regulation, making it harder to resist cravings and make rational choices” (NIDA. 2020).

3.“Changes in Brain Structure (Neuroplasticity and Damage). Chronic drug use rewires neural pathways, strengthening those linked to drug-seeking behaviour while weakening pathways involved in self-control. Some drugs (e.g., methamphetamine, alcohol) that are frequently used by people on OAT, cause neurotoxicity, leading to brain shrinkage and cognitive impairments” (NIDA. 2020).

4.“Increased Stress and Anxiety Responses. The brain’s stress system (amygdala, HPA axis) becomes overactive, making users more prone to anxiety, depression, and emotional instability when not using the drug. Withdrawal symptoms (irritability, restlessness, depression) reinforce continued drug use” (NIDA. 2020).

5.“Memory and Learning Deficits. The hippocampus, critical for memory and learning, is often damaged by chronic drug use (e.g., alcohol, opioids, cannabis), leading to cognitive impairments. Drug-related cues become deeply ingrained in memory, triggering cravings even after long periods of abstinence” (NIDA. 2020).

The consequences of chronic drug use include:

1.“Increased Tolerance and Dependence. The brain adapts to the drug, requiring larger doses to achieve the same effect (tolerance). Dependence develops, meaning the user needs more of the drug to feel normal and avoid withdrawal symptoms” (NIDA. 2020).

2.“Compulsive Drug-Seeking Behaviour (Addiction). Brain changes lead to compulsive craving and use, despite the negative consequences (legal, financial and health-related). Users also lose control over their behaviour, prioritising the drug use over relationships, work, and responsibilities” (NIDA. 2020).

3.“Mental Health Disorders. Chronic drug use increases the risk of depression, anxiety, psychosis (e.g., with meth, opioids, or cocaine), and cognitive decline. Some drugs (like cannabis or hallucinogens) can trigger long-term psychotic disorders in vulnerable individuals” (NIDA. 2020).

4.“Increased Risk of Overdose and Death. Opioids (heroin, methadone, fentanyl) depress the brain’s respiratory centres, leading to fatal overdoses. Stimulants (cocaine, meth) can cause heart attacks, strokes, or seizures” (NIDA. 2020).

5.“Social and Behavioural Consequences. Addiction often leads to job loss, financial ruin, legal troubles, relationship breakdowns, and homelessness. Increased risk of risky behaviours, such as unsafe sex, crime, and accidents” (NIDA. 2020).