by Email From Maggie Petito – 19.11.25

Neither the casino nor the four defendants admitted to knowingly laundering money for cartels or anyone else. But some investigators said that their actions helped bad actors hide the source of their illicit money.

“Federal laws that regulate the reporting of financial transactions are in place to detect and stop illegal activities,” said Carissa Messick, the special agent in charge for the Internal Revenue Service’s criminal investigations unit in Las Vegas, in a statement at the time. “Deliberately avoiding Bank Secrecy Act requirements is a form of money laundering.”

In a statement to CNN, Wynn Resorts said the company fully cooperated with the investigation and “immediately terminated the few employees involved because their actions violated the Company’s compliance program.”

“Wynn is committed to upholding the highest standards of integrity, compliance, and regulatory responsibility,” the Wynn casino said. “We accept responsibility for the historical deficiencies identified, have taken meaningful remediation, and are dedicated to ensuring that such failures do not reoccur.”

The cases of the four defendants that helped lead to Wynn’s historic settlement show how casinos have profited from having dirty money come through their coffers, and how drug cartels seek to legitimize the huge profits they generate from the sale of fentanyl and other drugs through legal gambling establishments, experts and investigators said. One prosecutor in Zhang’s case estimated that at least a hundred million dollars annually was being laundered through American casinos.

“Forty-eight hours ago, that was the proceeds of fentanyl,” said Chris Urben, a former assistant special agent in charge with the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Special Operations Division, speaking about some of the cash that Zhang and others moved through the Wynn and other casinos.

Although federal regulators and authorities have cracked down on banks and demanded tighter scrutiny on the cash deposits favored by cartels, regulators have been slower to apply that same pressure to casinos — despite their financial interest in looking the other way or even facilitating these crimes.

“They haven’t received as much scrutiny as financial institutions have in the past,” said Ian Messenger, founder and CEO of the Association of Certified Gaming Compliance Specialists in Toronto. “That is changing, with cases like Wynn.”

Hunger for cash

The schemes to move illicit money at Vegas casinos traced back to a simple problem: High-rolling gamblers from China — who are known to drop up to a million dollars on a single hand of blackjack — were having problems accessing their funds in the US.

A corruption crackdown by the Chinese government starting around 2016 led to stricter enforcement of rules prohibiting individuals from taking more than $50,000 a year out of the country.

How Chinese gamblers get illicit US cash to use at casinos

When big-money Chinese gamblers can’t get enough American cash to use at casinos because of Chinese government restrictions, they sometimes turn to a black market for the money. Here’s how middlemen in the US convert money from drug cartels and other illicit businesses into cash for them:

An “underground banker” drives around Las Vegas collecting money from customers who may have earned cash from illicit means – ranging from drug cartels to prostitution rings.

The underground banker pays them back for the cash by transferring the same amount, minus his fee, to a Chinese bank account, circumventing US safeguards.

A high stakes Chinese gambler arrives in Vegas, but he has a problem: He legally can’t bring more than $50,000 annually into the U.S. under Chinese law, and needs more to gamble.

The casino wants the gambler’s business. So a casino host calls the underground banker and asks him to bring cash, according to US authorities.

In a private room at the casino, the underground banker gives cash to the high-stakes Chinese gambler.

The Chinese gambler pays the underground banker back, plus a fee, by transferring Chinese money to a Chinese bank account — again evading US scrutiny.

The gambler takes that cash, which may have started with drug cartels, prostitutes and other illicit businesses, and turns it into chips at the casino.

For US authorities, this rule has created supersized demand among well-heeled Chinese visitors and expats. When they need large sums for purchasing real estate, buying a luxury car or other big expenses, many turn to underground bankers.

These illicit bankers, who are also often Chinese, have turned to criminal gangs such as Mexican drug cartels and prostitution rings, law enforcement officials told CNN.

In exchange for cash, the cartels and other providers are paid back through Chinese bank accounts that face no US financial scrutiny.

In recent years, these Chinese middlemen have essentially become the go-to bankers for the biggest players in the US drug trade, authorities have said, wresting control from Latin American interests in what has amounted to a bloodless coup.

And high-stakes Chinese gamblers quickly became important players in the financial scheme, authorities say.

The big break

In late 2018, Dave Mesler, a special agent with the Internal Revenue Service’s criminal investigation unit, got an intriguing tip from employees at another Las Vegas casino.

They’d noticed a strange pattern: A man would walk into the casino carrying a satchel and then would meet a host — a casino employee in charge of keeping high-value gamblers happy. The host would summon a high-roller, and the trio would disappear to a private setting like a hotel room. Then the man who came with the satchel would depart, often without having gambled.

Staff at the casino, which Mesler confirmed was not Wynn but declined to identify due to DOJ policy, eventually notified law enforcement about a handful of men all following the same pattern.

“The casino didn’t quite figure out what they were up to,” Mesler said, but “they realized these guys were up to something.”

Mesler and other investigators soon learned the IDs of four of the men: Lei Zhang, Bing Han, Liang Zhou and Fan Wang. All were Chinese nationals in their late 30s or 40s living in Las Vegas. (None of the men responded to CNN’s multiple efforts to reach them. )

Mesler, who at the time led the IRS’s Las Vegas Financial Crimes Task Force, subpoenaed their cell records. The results excited him so much he flew from his office in Las Vegas to San Diego to meet with a federal prosecutor.

“I found that these guys were talking to Wynn casino hosts multiple times a day every day,” Mesler said. “Hundreds a week. … I mean, I don’t even talk to my girlfriend this much.”

Investigators had already been interested in Wynn, a high-end resort with a sleek glass design with locations worldwide, including Macao – the only place in China where gambling is legal.

Investigators had earlier looked into bank accounts they suspected were being used by drug cartels to fund gambling at the casino, DEA sources said, but none of those probes led to any charges being filed. (Wynn said in its statement that the accounts were “established to allow out-of-state guests to make normal and customary payments to the Company” and that the casino followed all proper financial reporting procedures.)

Mesler believed something bigger was afoot with the new evidence involving the four Chinese men. “It was happening now – it didn’t happen years ago,” Mesler said. “This breathed a lot of new energy into the case.”

Mesler started reviewing surveillance footage from Wynn, and sure enough, the four men were making regular visits with casino hosts and high-rolling gamblers there.

With the evidence mounting in early 2019, other agencies joined the case: the US attorney’s office in San Diego, the DEA, the Department of Homeland Security and even the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department.

Through surveillance footage, undercover assignments and interviews with informants and the defendants, investigators were able to piece together a more complete picture of the sophisticated scheme.

Wynn casino and Mexican cartels

Investigators began watching as the four underground bankers or couriers working for them drove in and around Las Vegas and Los Angeles making cash pickups, law enforcement sources told CNN.

“They would take cash from anybody that had cash they didn’t want to deposit in a bank account for various reasons,” Mesler said.

The men would then shuttle the ill-gotten cash to Wynn and other casinos in Vegas, where they would meet with a casino host and an elite gambler from China for a hand-off.

“It didn’t always happen in a hotel room, but it could. It could happen in the hotel bathroom as well,” said Peter Fuller, a former detective in the Las Vegas police department who worked on the case. “It also happened in vehicles.”

Phone data seized from the four suspects showed they were frequently communicating with Wynn casino hosts, said Urben, the former DEA official — but also that some of their communications traced back to Mexican cartel operatives. He added that other intelligence, including surveillance and post-arrest interviews, also pointed to cartels as a significant source of cash.

CNN obtained an unclassified internal DEA document, which reported that agents suspected money launderers were feeding cash from Latin American drug cartels to Chinese gamblers, who were “reliable customers to purchase cash drug proceeds.” The intelligence report, which was shared with field offices across the country in 2021, also linked Vegas casino hosts with members of US-based drug trafficking organizations “seeking to launder drug proceeds.”

“The majority and the driver of this was Mexican cartel proceeds,” said Urben, who now works as a managing director at Nardello & Co., a private global investigations firm that specializes in corporate matters. “When I say that, I mean fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine.”

A Homeland Security investigator, who worked closely on the case and asked that his name not be used out of safety concerns, said much of the cash being sold by underground bankers to Chinese gamblers in Vegas at the time appeared to come from cartels.

It’s unclear how much the casino hosts or Chinese gamblers knew about the source of the money when coordinating the transactions, officials said.

But they all knew enough to be secretive about the activity, the Homeland Security investigator said, “so they must have known they were doing something bad.”

After using a Chinese social-messaging and mobile-payment app called WeChat to make a quick money transfer, the gambler would often take the cash, bring it inside the casino and exchange it for chips, officials said.

The end result was that everybody got what they wanted. The casino host got the golden-goose gambler to play at Wynn, the gambler received the cash, the “third-party” source was able to replace their dirty cash with a clean deposit in a financial institution, and the underground banker got his fee, all without having to send hefty dollar amounts across international borders.

In May 2019, investigators on the case carried out the first sting operation. It targeted Zhang.

Zhang had been lured to a Las Vegas casino hotel room by an undercover federal agent who called the money mover posing as a wealthy gambler looking to obtain $150,000 in cash.

As he made his way through the casino floor to the hotel room, agents working with Homeland Security Investigations waited in an adjoining room. Zhang had been instructed to show up alone, but he came with a woman. Zhang knocked on the door and the undercover agent answered.

The agents barged in.

“He looked very cool and suave,” said the Homeland Security investigator. “Cool sunglasses and hair. … Very Vegas.” The agents opened the satchel and discovered four brick-sized stacks of cash, the investigator said.

The woman, who had a handful of cell phones on her, was a “madam” who ran an escort service, he said. Two-thirds of the cash belonged to her, and she wanted to make sure the transaction went smoothly. The agents seized the cash; the woman was not arrested, he said.

That bust, he added, helped lead investigators to the other three suspects, who were arrested in similar stings throughout Las Vegas that summer.

The four defendants

With the evidence collected by Mesler and others, Zhang, Han, Zhou and Wang were charged in federal court between May and September of 2019 with operating an unlicensed money transmitting business.

Prosecutors said their scheme was just a fraction of the illicit money moving through casinos.

“The total magnitude of this problem, especially in Las Vegas, catering to high-roller Chinese gamblers who come into Las Vegas without easy access to United States cash, is certainly in the nine figures on an annual basis,” said prosecutor Mark Pletcher during Zhang’s sentencing hearing in 2020. “We’re talking about a problem in the hundred-million dollar range” yearly, he added.

In court, the defendants — who had all emigrated from China — described how they’d been drawn into the underground banking schemes because they needed money to help care for children or elderly parents, in a country where they had few connections and spoke little English.

By fall of 2020, all four pleaded guilty to a lesser crime than money laundering: operating an “unlicensed money transmitting business.” Investigators told CNN the money-laundering charge would require proving that the defendants themselves knew the source of the dirty cash they were bringing into the casino.

But another prosecutor, Daniel Silva, told the court that the activity “totally undermines the United States’ anti-money laundering laws.” The networks, he added, “are a huge, huge problem in the United States” and “will not be tolerated.”

Zhou, now 42, was ordered to repay the government $446,000. He was sentenced to six months in prison. The lightest sentence went to Wang, who received three months in home detention and was ordered to repay $225,000 for his role in the scheme.

A former professional poker player who also worked in the “junket” industry that brought Chinese gamblers to Las Vegas, Wang, now about 43, was charged last year with lying about his felony conviction while trying to purchase a semiautomatic assault rifle in Las Vegas, court documents state. He pleaded guilty to the weapons charge in April and was sentenced to time served.

The steepest forfeiture penalty went to Han, now 50, who was ordered to repay $500,000. Han told the courts he was granted asylum in the US in 2019 after suffering religious persecution in China for starting a church in his home, according to court records.

The stiffest prison sentence went to Zhang, now about 45, who’d claimed through his lawyer in court that he had no idea he was doing anything wrong. The judge handed Zhang 15 months in prison and ordered him to repay $150,000 – a formality as authorities had already seized that amount in the raid.

Fuller, the former detective with the Las Vegas police department, said it’s important to recognize the harm in the crime.

“You just can’t go take cash from anybody, because what ends up happening is, you end up taking it from Pablo Escobar,” said Fuller, who now works as a special agent for the IRS. “It’s basically the same thing that took place in the ’30s with Al Capone and all that, all the bankers and everybody. ‘Oh no, I, I don’t sell drugs. I’m not in organized crime. I just set up companies for people. I just move money.’”

Last fall, a little over two years after the last of the four men were sentenced, Wynn casino signed the non-prosecution agreement and admitted to its employees’ involvement in a range of schemes, including those catering to high-rolling Chinese gamblers. The casino, in a statement to CNN, said it was unaware of the details of the four individual criminal cases as they played out in court.

The agreement also highlighted earlier cases dating back to 2014 in which the Wynn casino “knowingly and intentionally conspired” with individuals – some with connections to Latin America – to set up illicit ways to get money to gamblers at the casino and to recruit foreign gamblers from places the US has identified as “major money laundering countries.”

In another scheme – referred to in the document as “human head gambling” – patrons who were prohibited by anti-money-laundering laws from gambling would stand behind a proxy gambler and give orders. One such patron had suspected connections to a transnational organized crime group.

Wynn casino’s involvement in the illicit activity wasn’t limited to casino hosts – it also included a company marketing executive and a senior executive of a company affiliate, the agreement says.

In its statement, Wynn said it has since made improvements outlined in its settlement, including adding high-level staff members to an office dedicated to enforcing anti-money-laundering laws, and establishing an independent compliance committee whose members are unaffiliated with the company.

An ‘explosion’ of Chinese money laundering

When Zhang and Han pleaded guilty in early 2020, they were the first in the US to be prosecuted for this form of underground banking, according to the DOJ.

Today, networks of Chinese underground bankers are the primary money launderers for not only the Mexican drug cartels, but organized crime groups around the world, including various Italian mafia groups, said Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on international organized crime with the Brookings Institution.

“Over the past eight years or so, you have this big explosion of Chinese money laundering in the states, in Mexico, in Europe,” she said.

Wynn isn’t the only casino that has been caught aiding criminals who evade banking laws.

In Australia, Crown Resorts casino was hit with a $300 million fine (in US dollars) in 2023 for running afoul of anti-money-laundering laws and continuing a business relationship with a junket operator despite the casino’s awareness of allegations the firm was connected to Chinese organized crime. “The company that committed these unacceptable, historic breaches is far removed from the company that exists today,” Crown Resorts said in a statement at the time.

In Canada, where this kind of crime has been rampant, a 2022 report by a government commission established to look into the issue revealed a common scheme in Vancouver that closely mirrors what investigators say was happening at Wynn: drug traffickers and Chinese loan sharks selling hockey bags filled with cash to Chinese gamblers who would wheel them into casinos to play a card game called baccarat.

Messenger, the gaming-compliance expert, said he wasn’t surprised that the historic Wynn settlement and similar cases haven’t attracted much public interest.

“The general public don’t typically have high expectations when it comes to the casino industry,” he said. “Everyone has Netflix. They’ve seen ‘Casino’; they’ve seen the other movies.”

The casino industry, however, has taken notice, and the culture of compliance with laws to prevent money laundering is improving, he said.

Even so, Messenger said, casinos – with their large volumes of cash and intensifying pressure to boost foot traffic and bring in high-rollers as online gambling gains in popularity – remain a rich venue for rinsing criminal proceeds.

“We see many, many cases of criminal funds or criminals attempting to deposit funds into the casino environment,” he said. “Not for the purposes of entertainment, but for the purposes of creating layers, creating explanations.”

Those criminal funds come from a business that has left a trail of devastation.

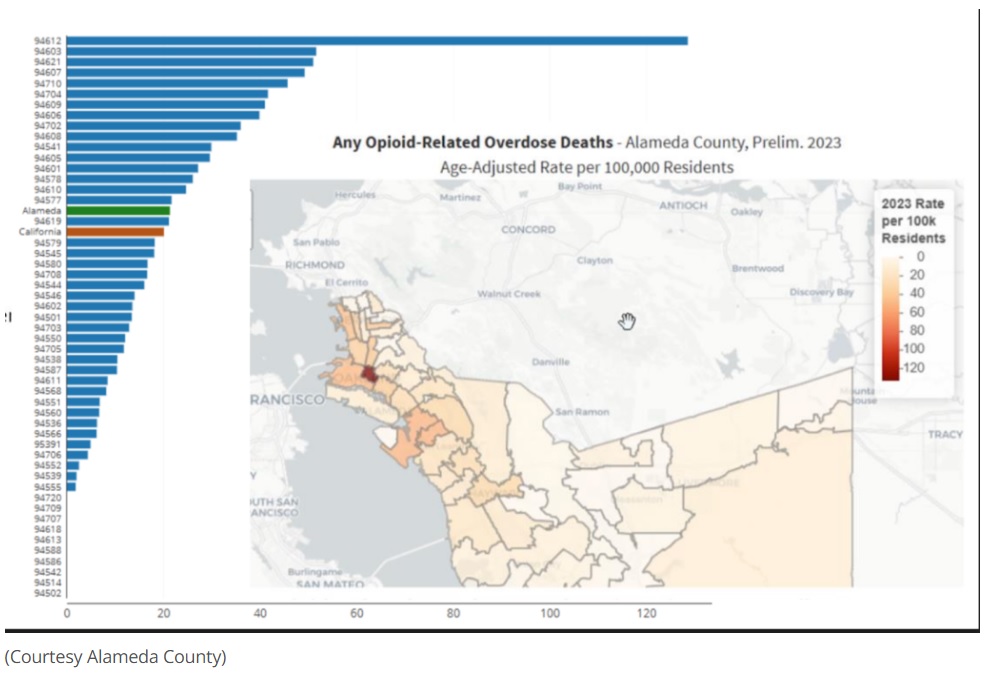

DEA official Brian Clark noted that the rise of Chinese money laundering coincided with a drug epidemic that in recent years has claimed over 100,000 lives annually in the US – the vast majority from opioids such as fentanyl.

“It’s all being fueled from this money laundering trade,” he said, “and it results in the death of Americans.”

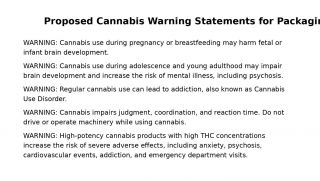

Source: www.drugwatch.org

The Princess of Wales is patron of The Forward Trust, a charity devoted to assisting addicts to remain abstinent from their drug of addiction. She has just spoken out forcefully against the view that addiction is weakness of will or any kind of moral problem.

“Addiction is not a choice or a personal failing,” she said, implying thereby that it was a medical condition like any other, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis. She said that “people’s experience of addiction in still shaped by fear, shame and judgment, and that this ought to change”.

I am sure that HRH meant well, and that she feels genuine sympathy for addicts; but unfortunately, her view is simple, unsophisticated, dehumanising and empirically false.

It is dehumanising because, by denying that addiction is a choice, it deprives addicts of their agency both in theory and to a certain extent in practice. If, after all, you persuade someone that he does not make a choice in doing something, you also persuade him that choice cannot prevent him from doing it. He is not a human being like you and me, but a helpless feather on the wind of circumstance.

This turns him into an object, not a subject, both to himself and others. Such a view is implicitly degrading, demeaning and far from compassionate. It implies the need for an apparatus of care to look after him, much as one would look after an animal in a menagerie, with kindness but not with much respect.

Take the case of the injecting heroin addict and think what he has to do and learn to become such an addict. He has to learn where to obtain heroin and how to prepare it. He has to learn to disregard its unpleasant side effects. He has to overcome a natural aversion to pushing a needle into himself. This is not something that just happens to him.

Moreover, not only do most addicts take the drug for some time before becoming physically addicted to it, but they are fully aware in advance of the consequences of taking the drug long-term. Addicts are not “hooked” by heroin, as they often put it; rather, they hook heroin.

It is untrue that addicts require a professional apparatus to overcome their addiction. Millions of people have given up smoking, though nicotine is addictive. During the Vietnam War, thousands of American soldiers addicted themselves to heroin and gave up, with almost no assistance, one they returned home.

In 1980, Porter and Jick pointed out that people treated with strong painkillers as in-patients in hospital did not go on to become addicts once they left hospital. This was unfortunately interpreted to mean that such drugs were not addictive; but, on the contrary, it shows that addiction, in the sense of continuing addictive behaviour, is not straightforwardly a physiological condition.

At the root of the Princess’s misapprehension is the post-religious or secular view that if a person is the author of his own downfall, he is due no sympathy or compassion. It is a highly puritanical view, and since we do not want to be puritans, we make the problem a medical one instead. But since we are all sinners and the authors of our own downfall, at least in some respect or other, this also has the corollary that sympathy or compassion is due to no one when he needs it.

The Princess appears to think that if you say to an addict that he has behaved, and continues to behave, foolishly and badly, you are necessarily saying to him, “Go away, darken my doors no more”. She seems to think that the truth, far from setting people free, will imprison them until someone comes along with a technical key to unlock them.

Of course, some addicts benefit from assistance, but not for the reasons the Princess supposes. Medication may reduce their physical sufferings, and if we take once more the example of injecting heroin addicts, we discover that they may well have so destroyed their relations with everyone – their families and friends – that there is no one to whom to turn if they desire to change their ways. They thus need a helping hand, but this is not the same as removing fear or stigma (a very necessary, though not sufficient, aid to civilised life). Though she did not mean them to be so, the Princess’s words were not so much demoralising, as amoralising.

Source: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gift/51db8fdbd5d80cb6